This concludes my 4-part series on The Wind Waker. A quick warning: this article is a bit on the heavy side, as it’s very personal. Please keep this in mind. Thank you for reading.

The Wind Waker is not a game about happiness.

Even with these last three articles trying to prove this statement true, I’m sure there are readers who disagree with it, because as many who have played The Wind Waker have mentioned in other articles scattered across the internet, The Wind Waker‘s spirit has made players happy.

I am also sure that there are those reading this who wonder why I have gone to such great lengths to prove this statement. The answer lies not only in my own fascination with the graphical style and how it expresses the themes of the game, but also in my own experience with The Wind Waker.

Indeed, I must agree with those who have written personal essays on this game. The Wind Waker made me happy, too — or, in more specific terms, The Wind Waker saved my life.

~

I had never quite thought of suicide in the sense that I wanted to commit it. However, stuck in rock bottom with seemingly no way out of it other than to finish my 6th grade year and move out of the school I was in that made my life into one that I had no desire to live, I grew completely apathetic to the thought of staying on this earth. I can honestly say that even at the young age of 11, I knew that if life had thrown a curveball that hit my chest and stopped my heart from beating, I would not have even cared. I had no intention of ending my own life, but if life had intended to give up on me completely, I wouldn’t have even wondered why. As tragic as it is even now to think of, in 6th grade, I had nothing left to live for.

One day, I asked a friend out of the blue if I could borrow The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker. I had no idea where this notion came from or what the title in question was about. I just knew that I wanted to play it suddenly.

3 months later, any suicide notes I had mentally written were erased from memory in favor of memorizing all the Wind Waker baton melodies. I used a burned CD and an old clock radio to wake me up to the rousing notes of “Journey” (the track that plays right as Link sets off with the pirates at the beginning of the game), and every walk home from school contained a song from the Wind Waker official soundtrack. I grew totally attached to each character: they were my best friends. I played violin as much as I could so one day I could be the next Makar. I loved it all. The Wind Waker did not help me “escape reality.” The Wind Waker became my life.

At the very least, it was one worth living.

2 years later, I had not passed the Earth Temple because I thought I lost Medli back in 6th grade. The very friend I had borrowed the game from two years previously did the honors, completing both the Earth and Wind temples for me in a day and giving me the opportunity to finally finish the title. My life had changed within two years, with on-and-off battles with depression and disappointment causing my road to be a bit rocky still. Knowing I needed this more than anything, I completed the game two months later, at the end of my 8th grade year.

To this day, I have not cried as hard as I did on June 10, 2011.

Once the credits rolled and I watched the wind guide Link and Tetra towards brighter horizons, I felt heartbroken and, if I may, a bit dead inside. I realized the wind was not behind me anymore. It was over, and I did not feel happy. I was not relieved in any way. I loved The Wind Waker for what it did to me, but its reign on my life ended there, and I knew it could never quite “love me” the way I did. It could not make me truly happy, and even though I tried as hard as I could, I could not move on.

~

The Wind Waker is not a game about happiness.

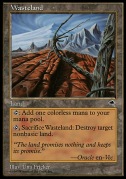

The Great Sea is hopeless, holding nothing for its inhabitants, whether Rito, Hylian, or human. It is not only a hostile environment, full of monsters of every shape and size, but a barren one. It is uncaring and unloving.

The cel-shading helps mask the true nature of the world, giving it a nice, bright look even when everything is everything but.

But why? Why does it lie to us? Why are we forced to perceive the world in such a light when this light completely contrasts it?

~

I felt lied to by this game until May 12, 2013.

It was the first time since June 10 that I had picked up The Wind Waker and played it again. It was two years later still, and I was in the same rut I had been in before, racked with disappointment and unhappiness.

Then I played the ending again.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3v10lERDBCI

“I want you to live for the future. There may be nothing left for you… But despite that, you must look forward and walk a path of hope, trusting that it will sustain you when darkness comes.”

It was a quote I had memorized a few months before, but my feelings on the game had not changed then. I still felt cheated, betrayed, like I had returned to the water’s surface from Hyrule and left to drown out in The Great Sea instead.

But as I listened to the King speak to me one more time, for the first time since the 10th of June, 2011, I realized the true intention of his words.

I finally felt the wind on my back again.

~

The Wind Waker is not a game about happiness.

The Wind Waker is about hope.

The graphical style of The Wind Waker does not lie to us. It moves us forward. It helps us realize that even in this wasteland, even in a place where there is nothing there for us, we can have hope in the form of bright colors and whimsical gusts of wind that, with the help of our baton, will always be behind us. Without the spirit of adventure we feel sailing along the barren, dangerous waters, we would have no reason to hold our tillers steady. If we saw The Great Sea through negative lenses, we would believe wholeheartedly that it holds no promise. The sun coming up over a non-cel-shaded horizon would mean nothing to us, the stars in the sky completely worthless.

The Wind Waker is a game about optimism. The Wind Waker is a game about looking forward.

“There may be nothing left for you…”

The Wind Waker is not about happiness. It cannot be about happiness: it is too realistic, too human to entertain the notion that happiness will always be in the air.

“…but despite that, you must look forward and walk a path of hope…”

Instead, The Wind Waker reminds us that even when happiness is nowhere to be found, even when darkness comes, we must look forward to seeing that sun rise. We must look forward and sail across the sea understanding that past every monster, there is a beautiful island just waiting to be explored.

“…trusting that it will sustain you when darkness comes.”

We must let the wind guide us, and we must always have hope.

~

Fin.